“Did you ever want to forget anything? Did you ever want to cut away a piece of your memory and black it out?”

That’s what nightclub piano player Al Roberts asks viewers in the 1945 film, Detour. And it’s what you may say after you’ve seen this low-budget noir movie filmed in a week or so with cheap sets, cheesy dialog and shortcuts in staging that make it treasure trove of cinema bloopers.

It’s not quite bad enough to be unintentionally funny—like some campy 1950s sci fi flick—but close. I’ve written about many of the superb noir pictures from the 1930s and ’40s and thought it would be interesting to look an example at the other end of the genre’s quality spectrum. Is Detour the worst of the worst? Some critics say no, even praise the film. Roger Ebert, however, was not one of them.

“Detour is a movie so filled with imperfections that it would not earn the director a passing grade in film school,” Ebert wrote. “This movie from Hollywood’s poverty row, shot in six days, filled with technical errors and ham-handed narrative, starring a man who can only pout and a woman who can only sneer, should have faded from sight soon after it was released.”

But it hasn’t.

Tom Neal plays Al Roberts, the piano player. He and his singer girlfriend, Sue, work in the same New York club. He wants to get married but Sue tells him she wants to go to Hollywood to become a star. They discuss the future as they stroll down a fog shrouded street.

A location shot in New York must have been too expensive, so a fog machine clouds the Hollywood back lot so heavily that the scene could be New York. Or Bakersfield. There aren’t even any establishing shots of Time’s Square or the Empire State Building.

Regardless, Sue heads for California and Roberts stays behind long enough to get lonely and decides to hitch hike across the country to see his girl.

To show Robert’s route, scenes of him thumbing a ride are interspersed with shots of a US roadmap. The camera naturally pans along the map from right to left—east to west. And when we see Roberts getting lifts, the cars are traveling right to left too—a cinematic convention to show westward travel.

The problem, however, is that the vehicles all appear to be right-hand drive, traveling on the left side of the road—English fashion. Ebert theorized that director Edgar Ulmer flipped the negative when he realized that conventional film grammar would call for right to left travel when moving west. As a result, in one scene when a truck stops to pick up Roberts, he jumps in on the driver’s side.

Eventually the direction of travel straightens out when Roberts is picked up by a guy named Haskell who tells him he’s a bookie on his way to California to make money so he can make a triumphant return to Florida where he lost everything on one race.

“One race. Thirty eight grand. They cleaned out my book,” Haskell tells Roberts. “How do you like that?”

“That was tough luck.”

“Yeah and I’m supposed to be the smart guy. You just wait. I’m going back to Florida next season with all kinds of jack. You watch those stinkers run for cover.”

Ann Savage and Tom Neal on the way to California pouting and sneering.

Roberts doesn’t seem to know what to make of the snappy repartee, but he sticks with Haskell who has been gulping some sort of pills that he keeps in the glove box. When Roberts spells Haskell at the wheel, he’s forced to pull over during a rain storm to put up the car’s convertible top. He gets out of the car and goes to the passenger side where Haskell is apparently sleeping. But when Roberts opens the door, Haskell’s unconscious body falls out, his head hitting a rock. He’s dead.

What is Roberts to do? Drive the body to the next town and call police? Flag down another motorist for help? Wish that cell phones had been invented in 1945?

Inexplicably, he feels trapped and reasons that asking for help and telling the story to police, is a bad idea. “They’d laugh at the truth and I’d have my head in a noose,” he says to himself in the self-pitying tone of his narration that runs throughout the movie. So what else was there to do except hide the body, steal the man’s money, car and clothes and take over his identity.

Later in his journey Roberts is reluctantly mixed up with Vera (Ann Savage), a scheming young woman with a taste for alcohol and a penchant for tantrums. Nothing good—or interesting—happens to anyone through the second half of the picture.

Poor acting, clichéd writing and threadbare sets aside, Detour has a following. Fans laud the film’s overarching, non-stop bleakness as perfect noir. But the plot’s wretched, dead-end future is only because Roberts is unbelievably foolish, taking the wrong turn at every crossroads.

At least one critic—and fan of Detour—deconstructs the plot and theorizes that Roberts is not telling us the truth. In literary terms he’s an unreliable narrator. Thus when he decides to dump Haskell’s body because the cops will surely blame him for a death that was likely of natural causes, he’s really misleading us. His motive is strictly greed, but he gives viewers a more sympathetic, less selfish (albeit farfetched) excuse.

Whether Roberts is stupid or greedy is immaterial. He’s still a sap—a name Vera uses on him later—in a plot that has nowhere to go. Deconstruction is not a tool to be applied to Detour. That would be like analyzing the existential subtext of Gilligan’s Island.

But it’s not all bad. One scene in Detour introduces a plot twist that’s so ingenious, so unexpected, it belongs in a different movie. Hitchcock could have built an entire film around this twist. In Detour, it’s quickly swamped by Vera’s hysterics, Roberts’ bad choices and the film’s general sloppiness.

Late in the movie Vera tells Roberts, “Your philosophy stinks pal. We all know we’re going to kick off some day. It’s only a question of when.”

And a question of whether or not you will have spent 67 minutes of your life on Detour.

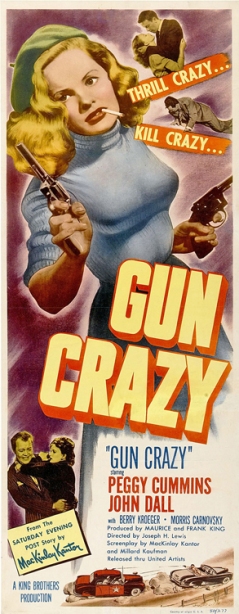

As we learn in the film’s first scene, Bart became a crack shot through years of shooting bb guns and larger weapons as a child. His obsession with guns—despite abject fear of hurting anyone or anything—leads him to steal a revolver from a store window. He’s caught and sent to reform school before joining the service.

As we learn in the film’s first scene, Bart became a crack shot through years of shooting bb guns and larger weapons as a child. His obsession with guns—despite abject fear of hurting anyone or anything—leads him to steal a revolver from a store window. He’s caught and sent to reform school before joining the service.